UK scientists achieve much-awaited “first plasma” in a bid to produce clean energy via fusion reaction

11/05/2020 / By Virgilio Marin

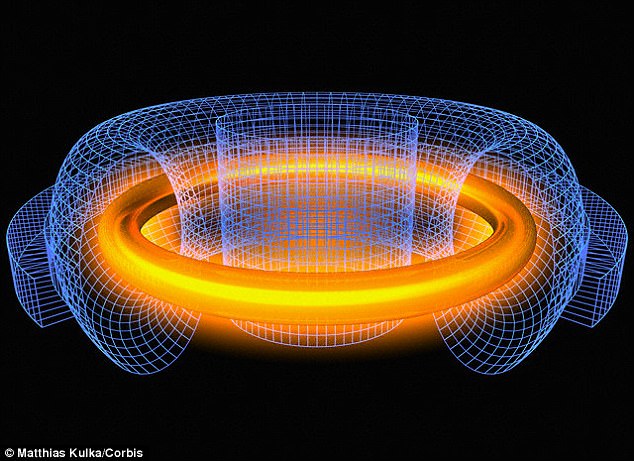

The promise of a cleaner, more abundant supply of energy gets a huge lift as scientists from the Culham Center for Fusion Energy in the U.K. achieved “first plasma” using the experimental fusion reactor, Mega Ampere Spherical Tokamak (MAST) Upgrade.

The scientists powered the MAST Upgrade on Oct. 29 after seven years of development. For the first time, they were able to demonstrate that the components of the fusion reactor could heat hydrogen gas into the plasma phase of matter.

The achievement marks a significant step toward harnessing clean energy from fusion reactors, something that scientists have been working on for several years. The findings from the experiment have direct applications for the development of fusion power plants.

“Backed by £55 million of government funding, powering up the MAST Upgrade device is a landmark moment for this national fusion experiment,” said Parliamentary Secretary Amanda Solloway of the U.K.’s Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS). The project was funded by BEIS’s Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council.

Fusion reactor can bring cleaner, abundant energy

Stars are powered by natural fusion reactions. Light hydrogen isotopes combine under extreme temperature and pressure, forming helium and releasing an enormous amount of energy. This process, however, can also be achieved by creating a ring of charged, super-hot plasma. The plasma is held in place by devices like tokamaks, which use magnetic fields to contain plasma and harness the reactions occurring inside it.

The MAST Upgrade, a refinement of a previous experimental tokamak called MAST, has an advanced spherical shape that’s expected to enhance the efficiency and performance of fusion reactors. With 90 percent new hardware, the reactor is capable of producing greater amounts of heat and stronger magnetic fields and plasma currents than MAST.

In their test-run, the researchers were able to produce plasma heated to around 1.8 million degrees. The reactor, according to the researchers, can eventually bring plasma to 10 times this temperature.

Once the technology is fully developed, fusion reactors are expected to improve power generation. For instance, a fusion reactor can produce around four times the amount of energy produced by a conventional fission reactor – the device used in nuclear power plants today.

What’s more, fusion reaction creates no long-lived nuclear waste, with its major by-product being helium – an inert, non-toxic gas. (Related: Turning heat into electricity: Engineers are working on technology that will harvest clean energy from pavement.)

The next step for the scientists is to test a key feature of the MAST Upgrade, an exhaust system called the Super-X divertor. Divertors are responsible for extracting excess heat from the plasma. This excess heat could damage the reactor’s components, increasing operation costs.

The researchers hope to address this issue through Super-X. It’s expected to bring a 10-fold heat reduction compared to what was achieved using current divertors. Should Super-X prove effective, it will make fusion power more affordable.

MAST Upgrade pivotal for other fusion facilities

The MAST Upgrade is meant to lead up to the Spherical Tokamak for Energy Production (STEP), the U.K.’s first prototype fusion power plant. This government-funded project is planned to be completed by 2040 and will have the same spherical shape as the MAST Upgrade.

“MAST Upgrade will take us closer to delivering sustainable, clean fusion energy,” said Ian Chapman, the chief executive officer of the U.K. Atomic Energy Authority.

“This experiment will break new ground and test technology that has never been tried before,” Chapman added.

The ongoing experiments on the MAST Upgrade will also inform the development of the world’s largest nuclear fusion facility, the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER).

ITER is a joint collaboration by several nations, including the U.S., China, Japan, Russia and member countries of the European Union. The reactor, which is currently being assembled in France, costs around $65 billion and is expected to start delivering energy by 2035.

For more news about clean sources of energy, visit NewEnergyReport.com.

Sources include:

Submit a correction >>

Tagged Under:

breakthrough, Clean Energy, discoveries, energy supply, fusion energy, fusion reactors, future science, MAST Upgrade, power plant, power supply, sustainable energy, tokamak

This article may contain statements that reflect the opinion of the author